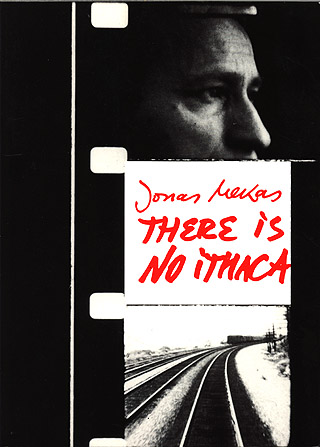

There is No Ithaca

Black Thistle Press, 1996

181 pgs

translated from Lithuanian by Vyt Bakaitis

This is the first English translation of two poem cycles that have become part of the classic repertory of modern Lithuanian literature. The translation is by Vyt Bakaitis.

Although Idylls of Semeniskiai was acclaimed under the Soviet regime as a classic for its depiction of rural life and the richness of its language, Reminiscences was banned for its "romanticizing" of the life of Lithuanian exiles.

"How many Europeans have lost their homelands in this turbulent twentieth century? Millions, and there seems to be no end to the condition of uprootedness, as the fate of Bosnia testifies. Those who become exiles lose not only their possessions. Trees, meadows, fields as seen in their childhood are taken from them. And yet, if they write about their lost countries, they are, in a way, privileged, and I am going to explain why, upon the example of Jonas Mekas' poems.

"Mekas found himself during the Second World War as a slave laborer in Germany. He was young, he survived. After the war, he shared the fate of many Displaced Persons who continued to live in Germany because their countries were overrun by the Red Army. In a Displaced Persons' camp he was writing poems about his lost Lithuania. His native village and four seasons, each with its labors in the fields and joys were his subject. Here we come to a secret of poetry written in exile. To be good, it has to make use of something going deeper than nostalgia. And that something is the power of distance.

" 'Distance is the soul of beauty.' This sentence of Simone Weil expresses an old truth: only through a distance, in space or in time, does reality undergo purification. Our immediate concerns which were blinding us to the grace of ordinary things disappear and a look backward reveals them in their every minutest detail. Distance engendered by the passing of time is at the core of the oeuvre of Marcel Proust. Distance in space and awareness that borders with their barbed wire separated him from his country allowed a young Lithuanian to write his Idylls. In a way his poems follow the model of a poem on the four seasons, The Year, by an eighteenth century Lithuanian poet, Kristijonas Donelaitis. Yet they have the warmth of the direct recollections of the author's childhood and adolescence in the house of his parents. It is good that Idylls, called by historians of Lithuanian poetry the best poetic work by Jonas Mekas, appear now in English translation. Mekas has been recently honored in America and France as a promoter of avant-garde cinema, of a movement created by independent film-makers, which, though marginal as compared with Hollywood, is seminal for the future of film art. His sensitivity to unrepeatable light, color, scents of his native region, in the north of Lithuania, as shown in Idylls is that of a visionary who lifts the most earthly details of reality to a higher level of intensity: this explains why he is both a poet and a poet of things observed and preserved on the film reel."

-- Czeslaw Milosz, from the Foreword of There is No Ithaca

"As I opened this book, I found myself wondering: What if Mekas weren't a great film maker? What if he hadn't worked and shown and clarified and prophesied the New American Cinema into the rich potential of art? What if he weren't friend of every friend, and the kindest man in Manhattan? What if he weren't even Lithuanian, sprig of a small elegant tree whose peasants speak like noblemen and laugh like sea-birds at the way history seems to have swamped them for a season? What if here were just some guy who wrote these poems, in 1947, nothing was happening to America then, Patchen and Vazakas and nobody paid attention to Williams, and here was young Mekas with his

Now the slightest shift in the air brings on

alder and juniper, over from the bushes,

with young buds, new leaves, catkins,

a smell of open water...

-- could I fault that, such sense for things held carefully between the lips, his deft echo of an epic line way back on the other side of time's caesura? What else could this be but poetry, the strict dance of mind speaking? There's a lot of country in these poems, a prisoner's nose for fresh air so seldom breathed, an exile's feel for mud and stubble that his feet understand. These poems are what an honest young man answered when the world was shouting louder than most of us have heard. He knew even then to judge the weight of words, the light and dark of them."

-- Robert Kelly